The year 2020 came in with a bang and it hasn’t let up yet. From the UK’s Brexit initiative, the US Presidential election primaries, a multitude of other celebrity or sports-related shocking news, and then culminating in the COVID-19 pandemic, collectively consumers have been facing a multitude of external uncertainties affecting their daily lives. Unfortunately, the distraction and chaos that is inherent during times of national or global upheaval provides the perfect breeding ground for cybercriminal activity.

Cybercriminals are opportunistic. They excel at taking advantage of disruptions in normal routines to social engineer individuals into falling for cyber threats, including phishing scams, charity scams, employee spearphishing, BEC scams, and even romance and elderly-targeted scams.

Phishing scams are already prevalent, and have been since the early 2000’s, targeting consumers to gain access to their personally identifiable information (PII) to access banking accounts, retail accounts, credit cards, etc. Over the years traditional phishing attacks have mutated to include many different types of scams, with a variety of targets, and using various obfuscating distribution methods – such as small, targeted or regional distributions, and geo-IP isolation.

An excellent, timely example of this change in cybercriminal technique was illustrated in February 2020 when Barbara Corcoran, an investor from the TV show Shark Tank, lost $388,000 due to her bookkeeper falling for a targeted email scam. The cybercriminal impersonated Ms. Corcoran’s assistant’s email address to request payment for a fictitious, but plausible, business transaction. By targeting a business entity, in this case, Ms. Corcoran’s real estate organization, the cybercriminal gleaned a significantly higher payday than if they had targeted random individuals through traditional, consumer-targeted phishing scams.

Business Email Compromise (BEC) scams are impersonation emails sent to selected recipients that appear to be from a legitimate individual, often requesting data, a wire transfer, or a change in Accounts Payable banking details. Over the past several years, BEC scams have become incredibly prevalent, as they have significantly more financial yield to the cybercriminal when targeting organizations versus individuals. According to the FBI, from June 2016 to July 2019, the global BEC scam landscape has grown to over $26 billion in losses.

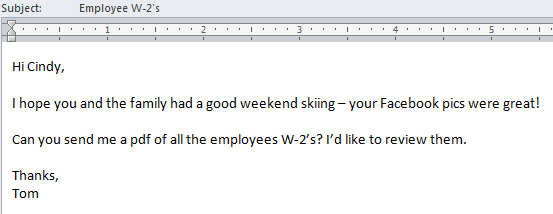

BEC scams vary in the theme, target, or method of transaction. Sometimes called Email Account Compromise (EAC) scams, the email account, business or personal, may be compromised but often the scam uses an impersonation email address rather than a misuse of the legitimate email address. Domain names are registered that look confusingly similar and, if the email is written convincingly enough, the recipient, often an employee, may not recognize that the mail didn’t come from the legitimate mail address. Executive impersonations are used commonly in employee spearphishing, where the recipient employee will typically feel compelled to respond quickly with the information requested – thus providing the cybercriminal with the information, the wire transfer, the W-2’s, or other intellectual property or payment term changes, the impersonating executive requested.

For past several years, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has kept a running list of scams that cybercriminals are using to target taxpayers for tax fraud. The list for 2020 includes a multitude of phone-based scams where the targeted victim is told their Social Security account or number is being suspended or cancelled, however that is simply the most prevalent scam of many. Additionally the IRS posts every year their list of dirty dozen “worst of the worst” tax scams and several on the list originate with cybercriminals – from phone scams, promises of inflated tax returns, phishing scams, and identity impersonation schemes.

Cybercriminals do their homework; they will commonly comb LinkedIn and other social media sites to find the information they need to specifically target an individual employee, such as in this example:

The IRS provides a valuable resource page for understanding these types of attacks and who to contact if an individual or organization has fallen victim:

- Email dataloss@irs.gov to notify the IRS of a W-2 data loss and provide contact information. In the subject line, type “W2 Data Loss” so that the email can be routed properly. Do not attach any employee personally identifiable information.

- Email the Federation of Tax Administrators at StateAlert@taxadmin.org to learn how to report victim information to the states.

- Businesses/payroll service providers should file a complaint with the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3.gov). Businesses/payroll service providers may be asked to file a report with their local law enforcement.

- Notify employees so they may take steps to protect themselves from identity theft. The FTC’s www.identitytheft.gov provides general guidance.

- Forward the scam email to phishing@irs.gov.

- See more details at Form W-2/SSN Data Theft: Information for Businesses and Payroll Service Providers.

Employers are urged to put protocols in place for the sharing of sensitive employee information such as Forms W-2. The W-2 scam is just one of several new variations that focus on the large-scale thefts of sensitive tax information from tax preparers, businesses and payroll companies.

Though there is a heavy focus on tax scams in the first four months of the year in the U.S., BEC scams can be used in many ways. One of the IRS’s dirty dozen tax scams is about fake charitable organization. Though this IRS article about false charities was published a year ago, it is timelier than ever as COVID–19 scams are starting to crop up in relation to phishing or malware distribution scams.

“Scam artists commonly use charities as a cover to lure honest people into providing money and sensitive personal information,” said IRS Commissioner Chuck Rettig. “Protect yourself, and make sure you are dealing with a reputable group before making a donation.”

Earlier this week, the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre posted an alert to consumers to be aware of online safety best practices as cybercriminals are exploiting consumer fear in relation to the COVID–19 pandemic. The NCSC warned that most scams are in the form of emails and encourage the recipient to click a link for an update to the pandemic and the link then download malware to the consumer’s machine. In February, the World Health Organization also posted a warning regarding impersonation scam emails as well.

Organizations can help to reduce consumer and employee victims from scams by following these guidelines:

- Provide employee education and awareness about cybercriminal scams. Employee empowerment is key to fighting social engineering tactics and helps the employee become a savvier consumer as well. Each employee must understand that they are the first line of defense in protecting themselves and their employment organization; natural skepticism for out-of-the-norm communications should be innate.

- Employees (and all consumers in general) should be suspicious of social engineering derived pressure to take urgent action or action outside of normal business practices. Cybercriminals thrive when they can convince a victim to operate outside of normal protocols.

- Train team members to hit “forward” instead of “reply” so they are forced to type or select the correct “To:” email address from a corporate list. This can often stop a scam attempt immediately.

- Pre-establish internal checks and balances to prevent one person from being able to send a wire transfer or email sensitive information such as an entire employee roster of W-2’s.

Business email compromise scams, email account compromise scams, and employee Spearphishing attempts are prevalent and increasing globally because they are so successful. It’s one email to one person. Detection is limited, and the threat actor is really counting on the human element to not look at the sending domain. Consumers use email every day; but, how often do recipients double-check the sending email address? Not often, and $26 billion in losses over the last 3 years proves it.